News July 21, 2021

College Athlete Merchandising Poised to Explode

A new ruling finally allows NCAA athletes to profit from their name, image and likeness. The promotional opportunities are vast – but so are the questions.

Three days before Independence Day, college athletes were finally granted a different sort of freedom: the ability to profit off their name, image and likeness (NIL).

After a Supreme Court decision that the NCAA can’t limit education-related benefits (such as computers and paid internships) that colleges can offer their athletes, the NCAA’s Division I Board of Directors reversed its longstanding, controversial policy on student athletes being prohibited from receiving compensation.

What pressed the NCAA’s hand – after decades of resistance – is the fact that eight states had laws or executive orders going into effect July 1 that allowed college athletes to earn money. (More than a dozen other states have passed similar measures with later effective dates.) In the absence of a uniform federal law, the smorgasbord of different laws threatened to create advantages for some schools over others. After all, schools in states with legal guarantees that students could potentially earn money would be better positioned to recruit prospective players.

In this episode of the Promo Insiders podcast, Senior Writer John Corrigan speaks with Steve Flaughers, owner of Proforma 3rd Degree Marketing, about his NIL concerns, including the licensing challenges.

As such, the NCAA enacted the interim policy until a federal law arrives. Overnight, more than 480,000 student athletes in the United States had the ability to become entrepreneurs.

“It’s impossible to overstate the importance of this development,” says J. Michael Keyes, partner at the international law firm Dorsey & Whitney. “By some estimates, the sports merchandising market over the last few years hovered around $15 billion. It’s about to get a lot bigger very soon.”

The opportunities are plentiful, as college athletes can now license their name to promote brands, sponsor events and campaigns and launch their own merchandising companies. “This will exponentially grow the promotional products industry,” says Ivan Parron, founder of PARRON Law Sports & Entertainment.

Parron, who recently represented NCAA players at the NBA Draft Combine, immediately sees a couple major benefits in which branded merchandise would play pivotal roles. “NIL will do miracles for women’s sports and is a huge opportunity for brands to get involved with female athletes,” he says, arguing that women often develop loyal followings as college athletes, but typically make much less money than men if they turn pro.

“I also think non-traditional sports, the ones you see at the Olympics, will get more exposure and potentially build strong fan bases,” Parron says.

With football and basketball as the top revenue-producing college sports, those athletes are sure to be highly sought after by major brands. Some industry experts expect the most prominent players to charge $1,000 or more an hour for endorsement work or appearances, The New York Times reported.

However, today’s marketplace is so fragmented that there are opportunities for athletes involved in other college sports, such as tennis, soccer and lacrosse, to still make a fair amount of money from their NIL, especially from local businesses like restaurants, car dealerships and sporting goods stores.

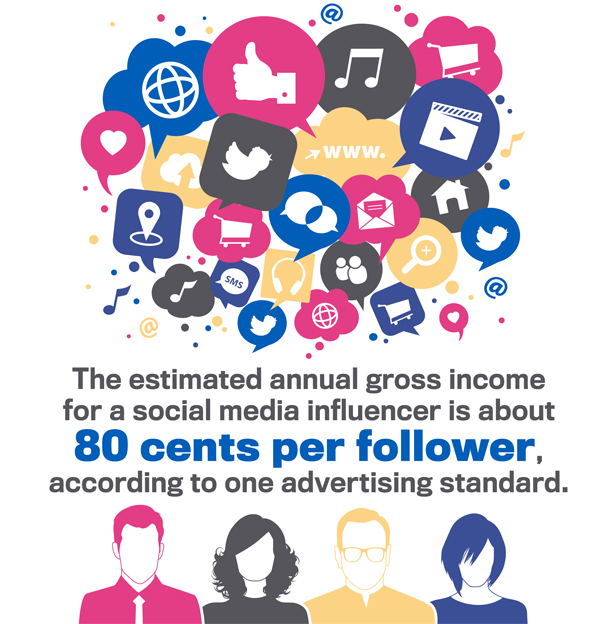

“This ruling will generally increase the visibility of college sports,” says Allen Adamson, co-founder and managing partner at the marketing strategy and activation firm Metaforce. “More buzz means more merchandise. Social media will play a huge factor, as popular athletes will influence followers into wanting a school’s mug or hat or T-shirt.”

Similar to how cities and states rely upon professional athletes and celebrities for location-branding activities, now there’s a whole new segment of spokespeople at their disposal. Consider Trevor Lawrence, the superstar quarterback for Clemson who was taken number one overall in this year’s NFL draft. If this was 18 months ago, Lawrence could have been South Carolina’s biggest ambassador, says John Boyd, principal of the management consulting firm The Boyd Company.

“If you’re high-profile, it’s your responsibility to tell your story and products are a part of that,” Boyd says. “Sneakers, jerseys, nutritional products, licensing for video games and apps. You’ll be bombarded with opportunities now.”

And you can bet promotional products will be part of the mix.

Slam Dunk for Promo

Even before the policy and laws went into effect, some college athletes had already prepared to cash in.

Georgia running back Kendall Milton launched his KM2 clothing line brand, partnering with Seven Six Apparel Co., which designs apparel for sports markets around the Southeast U.S. Jordan Bohannon, a basketball player at the University of Iowa, also launched his own clothing line called J3O Apparel. University of Wisconsin’s starting quarterback Graham Mertz unveiled a trademarked personal logo on his social media accounts, and then launched his own official store and licensed apparel collection.

Excited to announce that I am officially releasing my wearables website! Hope you all enjoy!

— Graham Mertz (@GrahamMertz5) July 1, 2021

Check out my official wearable collection at the link below:https://t.co/z8XCVfpP4o

Thank you for your support. It’s only the beginning! pic.twitter.com/aQae7ce05u

Even the players’ furry friends are getting in the action – Arkansas wide receiver Trey Knox and his Siberian Husky Blue inked a deal with PetSmart.

“This is no different than anyone selling merchandise, whether it’s a YouTuber, someone on Twitch, a band, a school or a retailer such as Target,” says Jeff Becker, president of Top 40 distributor Kotis Design (asi/244898), which is a collegiately licensed vendor. At the end of the day, Becker says, “it’s just someone selling something.”

Distributors and merchandising brands have already reached out to college athletes from all three divisions, offering a plethora of products and strategies to exercise their NIL rights. “I see nothing but a positive for the promo industry,” says Lucas Guariglia, owner of Rowboat Creative (asi/313715), which is extremely active in the burgeoning influencer space and has also worked with numerous sports clients. “The opportunity for more brands popping up and more need for promotional products and merchandising is a good thing for us all.”

“These student athletes have their finger on the pulse of what’s hip. From a marketing perspective, they provide a lot of value.” Amobi Okugo, professional soccer player and founder of A Frugal Athlete

“Just as our industry became the initial go-to for PPE, we will be the front line for change in what ultimately will be new collegiate licensing opportunities,” says Jon Saferstein, owner and COO of Top 40 supplier Sportsman Cap and Bag (asi/88877) in Lenexa, KS. “We always look for various opportunities in the college market, but this generation embraces social responsibility and will be looking for products like our new sustainable cap styles to help them build better brands.”

Natalie Welch, a sports business professor at Linfield University, has already seen a couple athletes donating a percentage of their branded merchandise to charity. She expects that to become a hot trend over the next few months, as college students tend to be very passionate about social causes.

“This ruling will force athletes to be more collaborative and creative while finding partners doing cool stuff,” Welch says. “We’ll see more athletes creating a product line or apparel line within an established brand. Right now, it’s just about getting your name out there, but long term, it will have to be more strategic to be sustainable.”

In addition to their presence on social media and in their community, student athletes offer another benefit for advertisers: youth. “Most brands are always trying to reach the younger demographic,” says Amobi Okugo, professional soccer player with Austin Bold FC and founder of financial consultancy A Frugal Athlete. “These student athletes have their finger on the pulse of what’s hip. From a marketing perspective, they provide a lot of value.”

Steve Flaughers, owner of Proforma 3rd Degree Marketing (asi/300094) in Canton, OH, has targeted the college sports market for years. Although he sees the potential in college athletes selling their own branded T-shirts and bobbleheads, he’s concerned about licensing issues that can arise.

“Students don’t seem interested in wanting to learn the licensing aspect of the products,” Flaughers says. “I assume if allowed, they will sell anything and everything that they can. This could pose a serious problem for the universities. Would they fine their own student athletes the same as they would us licensed suppliers? If the university feels they’re losing a great deal of revenue, will this mean licensing fees skyrocket to make up for that loss of money they have made off the student athletes?”

On June 30, the Collegiate Licensing Company – which governs the use of college sports trademarks, such as university names and logos – sent notices to licensees, such as Flaughers, with updated guidelines for pursuing NIL programs co-branded with university trademarks. Unlike the original policy proposed by the NCAA, many state laws and university policies allow the student-athlete to use logos and brands only with approval from the institution.

“Merchandise that does not contain university IP marks, brand elements, names, etc. but contains student-athlete NIL, must be licensed/approved directly with student-athlete, as CLC does not represent student-athlete brands,” the CLC stated.

The Wild West

Until Congress steps in or the NCAA is forced to issue a permanent decree, many questions regarding NIL have been left unanswered.

How will revenue-sharing agreements work? Will student athletes be allowed to wear their school’s name or logo in their own promotional activities? Will these athletes have to go through vendors pre-approved by their athletic department? What happens when an athlete promotes, say, Nike, but the school’s athletic department has a partnership with Adidas?

“Many politicians seem to think this should be a 50/50 split between the schools and the student athletes, but that probably doesn’t accurately reflect what it costs to maintain a major scholastic athletic program,” says David Jacoby, intellectual property law attorney with Culhane Meadows. “However, there’s no way you could make all this money without the players.”

It’ll resemble the Wild West for a while, says Marc Kidd, CEO of marketing agency Captivate. Kidd helped create the NCAA corporate partner program while serving as president of Host Communications during the 1980s and ’90s. “Clearly, each school has protected trademarks, but if I was a player at the University of Texas, can the school keep me from wearing burnt orange in advertisements?” Kidd says. “It’ll be interesting to see how this is policed and administered throughout the country.”

“I see nothing but a positive for the promo industry. The opportunity for more brands popping up and more need for promotional products and merchandising is a good thing for us all.” Lucas Guariglia, Rowboat Creative

Attorneys Andrew Dana and Alonzo Llorens, leaders of Parker Poe’s sports and entertainment industry team, say the NCAA decision is long overdue. But there needs to be uniformity with a federal law because each state has different laws, and in those that don’t, schools have been left to make up their own rules.

“If you’re deciding which school to go to and one has limitations, that leads to unequal decision-making and hinders that school’s ability to be competitive,” Dana says. “That disparity needs to be evened out.”

With so much uncertainty regarding the rules and regulations, some promo firms are reluctant to plunge headfirst into the neoteric market. “We want to avoid the chaos,” says Bruce Jolesch, president and CEO at Garland, TX-based PXP Solutions (asi/78964), which already works with distributors who service the NCAA. “There are all types of unknowns that frankly haven’t been addressed yet. And no matter what happens this year, everything will change again in 12 to 24 months.”

San Francisco-area distributor Harry Ein, owner of Perfection Promo an affiliate of iPROMOTEu (asi/232119), works with professional sports teams, but doesn’t perceive the NCAA ruling as an opportunity to expand his business. “It’s bigger news for digital printing companies, like one-off shops,” Ein says. “I could see college athletes using social media to promote branded merch that could be printed-on-demand, but I don’t see them needing to hold inventory or anything like that. There’s only a handful of athletes around the country who could demand that type of interest and justify the cost of setting something like that up.”

Just Say No

Just Say No

In the wake of the NCAA’s new NIL policy, the branding possibilities are endless for student athletes. But college athletes aren’t free to endorse all products and brands. The NCAA, schools and state legislatures have unanimously stated that certain categories of companies/products, such as alcohol, tobacco, firearms, drugs and CBD, are off-limits for these athletes. If players want to endorse those brands, they’ll just have to wait until they get to the big leagues.

Fresno State was among the first athletics departments to partner with Opendorse – a sports technology company that maximizes endorsement value for athletes – providing all of its student-athletes with the education and tools to maximize NIL rights. Fresno State twins Haley and Hanna Cavinder, star guards on the Bulldogs’ women’s basketball team, have already signed deals with Boost Mobile and Six Star Pro Nutrition. They’re considered among the top five most marketable players in women’s college basketball, according to Opendorse.

The twins’ earnings potential continues to explode on social media with a shared TikTok account that currently has 3.3 million followers, up from 2.9 million in April. They also have individual Instagram accounts with more than 250,000 followers, up from around 185,000 in April. A valuation prepared by the marketing platform estimated the Cavinders’ shared TikTok at more than $520,000 annually and their individual social media accounts at around $45,000 annually, The Fresno Bee reported. A single branded post on TikTok would be worth around $35,000.

By comparison, Saul Jimenez-Sandoval, the newly hired Fresno State president, is paid $348,423 (excluding benefits and other perks). Jaime White, the Bulldogs’ women’s basketball coach, makes $262,563 in base salary.

“Female athletes are more likely to have a significant following on social media,” Dana says. “By focusing on their brand identity and social media engagement, they created these followings before the ability to monetize, so they’re in a prime position to capitalize.”

Of course, with great power comes great responsibility. While student athletes have already been splitting their time between academics and sports, now they add entrepreneurship to the equation. Dana and Llorens suggest they build a support team before embarking on this endeavor, hiring legal counsel, a financial consultant and other experienced business professionals who they can trust.

“This is their first time making significant income, so they need advice on how to spend, invest and store,” Llorens says. “There’s eagerness to monetize themselves, but they need to temper that with a prudence to enter into these agreements with eyes wide open. They need people around them to make sure they don’t get taken advantage of.”

“If you thought the NCAA was bad, wait until you get before the IRS,” Dana adds.

Although it’s already too late for some eager college athletes, every marketing expert shares the sentiment that less is more. Instead of taking every deal that comes in, it’s important to be selective so you don’t dilute the value of your brand.

“You don’t want to have look back in a few years and see your social media posts plugging a bad restaurant chain,” says Larry Mann, partner at rEvolution, a sports marketing and media agency. “You would never eat there, but you promoted it for $300. Be authentic and work with companies you believe in.”