Education | June 17, 2022

Professor Delivers Powerful Insights on Juneteenth and the History of Enslavement in the United States

Dr. Artress Bethany White, a poet, literary critic and professor at East Stroudsburg University, led a webinar for ASI employees in which she provided insights on Juneteenth and the broader harsh realities of American slavery.

The written receipt contained only a few words. Still, generations of a family’s suffering echoed between the lines.

Inked in 19th century cursive, the receipt documented the sale of an enslaved African-American woman and child to a white female owner. Brief, to the point, summarial, it was the unsentimental language of transaction, as if the purchaser was buying an agreed-upon amount of grain – or an animal.

Dr. Artress Bethany White, East Stroudsburg University

Only the commodities being purchased weren’t commodities at all. They were human beings. They were the ancestors of Dr. Artress Bethany White. The poet, a literary critic and professor at East Stroudsburg University, found the document while conducting research on her family. She held it in her hand. It carried the weight of history, searing into her heart the agonizing realness of her family’s enslavement.

“It was very emotional for me,” said White. “This document made it all a very stark reality.”

White shared this powerful personal confrontation with one of the darkest periods in America’s history during a frank and illuminating webinar for ASI employees on June 17. Hosted by ASI’s Diversity & Inclusion Council, White’s talk used the Juneteenth federal holiday as an entry point to discuss the broader realities and ramifications of slavery in the United States.

The approach was appropriate, for as White shared, Juneteenth isn’t just for celebration. It should also serve as a time for reflection and education on American slavery and how the legacy of that immoral institution has shaped society to this day.

“Part of celebrating Juneteenth,” said White, “is learning about the history of slavery.”

A Short History of Juneteenth

Juneteenth is a holiday that commemorates the end of slavery in the U.S. Also known as Emancipation Day or Freedom Day, Juneteenth gets its name by combining the words “June” and “Nineteenth.”

On June 19, 1865, Union troops arrived in Galveston, TX, to take control of the state and see to it that enslaved people would be free. While the Civil War had ended two months earlier with victory for the anti-slavery Union, and the Emancipation Proclamation (which freed some but not all slaves) was issued two and a half years earlier, the practice of slavery persisted in Texas. Technically, it ended that June 19 when Union General Gordon Granger stood on Texas soil and read General Order No. 3.

“Although emancipation didn’t happen overnight for everyone – in some cases, enslavers withheld the information until after harvest season – celebrations broke out among newly freed Black people, and Juneteenth was born,” reads an account from History.com. “That December, slavery in America was formally abolished with the adoption of the 13th Amendment.”

While deeply significant, the holiday has long gone overlooked. Still, as the social justice movement has gained momentum in recent years, Juneteenth is starting to get the attention it deserves. President Joe Biden, for example, declared it a federal holiday – an important step toward propelling wider-spread recognition and celebration.

The Realities of Enslavement

As awareness about Juneteenth grows, the holiday can serve as a strong foundation for educating about slavery in the U.S. and the experience of people of African descent who suffered enslavement. White’s webinar keyed in on this aspect.

She discussed, for instance, the structure of slavery. This consisted of European/European-descended American traders corralling Africans and then coercively transporting them by ship to the U.S. and Caribbean, where they were sold into enslavement. They were then forced to work on plantations, pressed into the hard labor that allowed commodities like sugar to be farmed and sold to white society in Europe and the U.S. White noted that the conditions on ships were horrific. The enslaved were packed in and restrained, left amid human waste. “A lot of people died,” White said.

Life was often grueling for those who survived. It was typical, White said, for the enslaved to receive only the bare necessities in clothing and food; doing so kept costs down for owners.

Physical means of oppression – from whippings and muzzles, to restraints and painful collars – were used to discipline and demean enslaved people. There were laws against teaching enslaved persons to read and write. Families could be separated if an owner decided to sell a particular individual – a threat that some “masters” held over the heads of the enslaved to coerce conformity to the slave system, White said. Freed men and women were sometimes re-enslaved.

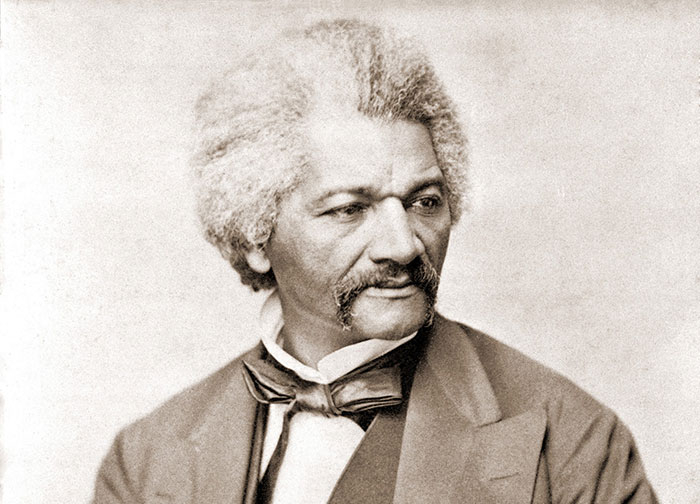

Frederick Douglass was an author, social reformer, abolitionist, writer and statesman who escaped enslavement.

Through it all, however, African-Americans weren’t passively accepting their state of enslavement – a point White was keen to emphasize. “They were serving as advocates for their own freedom,” she said. “Efforts were being made to gain freedom, in the north and the south. They weren’t just waiting to see what history would bring.”

Accounts of the diverse experiences of African-Americans in enslavement, including those efforts to break free, are vividly detailed in what are sometimes called slave narratives – accounts written by people who endured enslavement. During her talk, White referenced works from authors such as Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs and Olaudah Equiano. She noted that narratives from enslaved people aren’t typically required reading in school. She thinks they should be, and she encouraged attendees to read the accounts.

“A reason slave narratives are not taught is because they tell the truth about the system,” White said.

According to White, part of the truth included that teenage girls as young as 14 were “bred” – meaning intentionally impregnated, often by owners or their overseers, so they would produce children that would become the property of masters, thereby offering more free labor on plantations, White said.

This practice appeared to pick up after the international slave trade became illegal and plantation owners needed to replenish their pool of free labor, according to White. It also created complicated personal dynamics, as some enslaved people were blood relatives to their oppressors, something that was true for members of White’s family.

While far from the only other important component of White’s talk, another significant point of emphasis the professor made was to distinguish between the term “slave” and “enslaved.”

“‘Slave’ makes you think they were born to be slaves – that they were a lesser form of humanity,” White explained. “‘Enslaved’ puts the onus on the people who purchased and traded in human beings.”

It’s one of many points from White’s talk to reflect on.