Awards April 01, 2016

Will China's Economy Crumble Its Sourcing Empire?

As an old expression proclaims: When China sneezes, the world gets a cold. And right now, China is sick. “A hard landing is unavoidable,” says George Soros, one of the world’s foremost investors. “I’m not expecting it, I’m observing it.”

>>Back to the Big Book of Questions

China’s current economic upheaval is going to impact sourcing patterns for industries across the globe. Its slowing economy is bringing its dominant trade position out of high orbit and back to Earth. This recent turbulence, coupled with larger systemic changes, are forever changing China’s role in the global supply chain. And the promotional products industry is not immune to these changes.

The World’s Factory

The majority of the promotional products upon which U.S. buyers have come to depend on are produced in China – writing instruments, computer and electronic goods, drinkware, picture frames and much more.

According to the Department of Commerce’s 2015 figures, China exported $2.7 billion worth of flash drives and other solid-state storage devices to the United States – almost three times more than Taiwan, the next largest exporter. Similarly, China exported $252 million worth of picture frames to the U.S., 10 times more than the next largest country. Drinkware? Nearly $190 million, six times more than Thailand. The $263 million worth of ballpoint pens were 60% more than Japan. (While a good portion of wearables such as garments and hats are produced in China, countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh have established themselves as sizable exporters, since labor is more affordable and textiles thrive on the cheapest labor.)

The promotional products industry depends on China. But it’s not the only one. For the past 35 years, since Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping threw open the doors to the world, China has evolved into the world’s factory as it welcomed investors and manufacturers to set up facilities. This monumental policy shift fueled double-digit annual GDP growth since the early 1990s. China’s massive workforce, which most recently stood at more than 800 million, has powered these factories and guaranteed affordable and plentiful labor.

The promotional products industry depends on China. But it’s not the only one. For the past 35 years, since Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping threw open the doors to the world, China has evolved into the world’s factory as it welcomed investors and manufacturers to set up facilities. This monumental policy shift fueled double-digit annual GDP growth since the early 1990s. China’s massive workforce, which most recently stood at more than 800 million, has powered these factories and guaranteed affordable and plentiful labor.

These factors have rendered China the largest global exporter to many of the world’s economies, including displacing Canada as the largest trading partner with the United States. In 2006, China’s exports stood at $343 billion. By 2015, total bilateral trade with China ballooned to $598 billion, representing a 74% increase over 10 years.

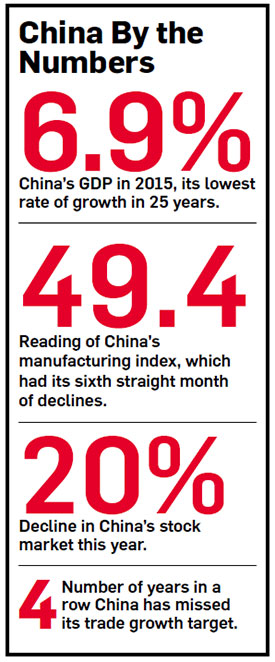

But the China growth engine has finally seemed to hit the ceiling. The GDP grew at its slowest rate in 25 years, falling to 6.9% from 7.4% in 2014. And the International Monetary Fund projects further declines in GDP growth, with forecasts of 6.3% growth in 2016 and 6% in 2017.

These GDP figures are being adversely affected by China’s collapsing global exports. The first signs of weakness appeared in March 2015, when its overall global exports fell by an unprecedented 15%, and continued to experience year-over-year monthly declines throughout the remainder of 2015 and into this year. Manufacturing continues to struggle; a much-watched index declines for the sixth straight month with little evidence of reversing course.

China’s economy is still growing, but these economic warning bells have instilled panic in investors both inside the Red Curtain and abroad. Since the beginning of the year, the major indices for the Chinese stock market have declined more than 20%. On several occasions, trading has been halted as daily declines reached the 7% maximum. On January 7th, trading reached this threshold in 14 minutes, marking the shortest trading day in Chinese history.

Sourcing Shift

While many are fearful of how a China slowdown can impact the global economy, others see it as a much-needed course correction. Brookings Institute foreign policy experts David Dollar and Michael E. O’Hanlon say the underlying mechanism of the Chinese economy has switched from an “investment-heavy growth model to a more sustainable growth-based one.”

“The superhuman leaps that China and its military have been taking needed to decelerate, for lots of reasons,” wrote the pair in a January article. “Investors around the world might be taking a short-term hit as the Chinese slowdown comes into clearer focus. But whether they realize it or not, they will benefit in the end from a moderate slowing of the Chinese behemoth that puts it on a more sustainable and stabilizing path.”

That paints an optimistic picture for China’s future, but it also hints at the severe changes the country’s economy will undergo to reach that point. China’s industrial-based approach is giving way to a consumer-based economic future. And specifically within manufacturing, China is reorienting from low-value added production toward technology, engineering and services. The country recently launched China 2025, the first of a three-part plan (concluding in 2049) that aims to put China in direct competition with countries like Japan and Germany for advanced manufacturing. By 2020, China aims to have a passel of technologically-advanced industries, (including green energy, medical devices, aerospace innovation and high-speed railroads) represent 15% of its GDP.

Under this major policy, attention will be diverted from lower-value added sectors like promotional products. In the short-term, other influences will affect China’s position.

For example, China has been excluded from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), between North American countries and a handful of Asian and South American countries (Australia, Vietnam, Malaysia, New Zealand, Peru, Chile, Singapore and Brunei). The TPP is part of President Obama’s “pivot to Asia,” and it will drastically reduce tariff and non-tariff barriers between the signatory countries and will result in increased trade between these parties. Although President Obama faces an uphill battle in Congress to ratify the final agreement, when it is eventually passed, it will shift sourcing patterns through these countries and away from those excluded from participation.

In addition, China devalued its currency last August in a move likely designed to bolster faltering exports and its manufacturing sector. However, it has raised the ire of its trading partners – including the U.S., where estimates are that currency manipulation by Asian economies over the last 10 years has cost the United States up to 5 million jobs. In September 2015, a bipartisan Congressional group sent a letter to President Obama urging a response to not only China, but also Vietnam and South Korea. The U.S. could respond with countervailing duties, which will effectively eliminate the currency benefits related to devaluation.

The most important factor? The rising price of Chinese goods, driven by increased labor costs. “There is that factor that prices are going up, because they have to pay their people more money now. Pure and simple. They can’t get the people, and when they get them, they’re not going to work for peanuts like they used to,” says Craig Wolfe, president of CelebriDucks (asi/44398), which sources 75% of its custom rubber ducks from China but handles art pre-production and the remaining 25% in the U.S.

The most important factor? The rising price of Chinese goods, driven by increased labor costs. “There is that factor that prices are going up, because they have to pay their people more money now. Pure and simple. They can’t get the people, and when they get them, they’re not going to work for peanuts like they used to,” says Craig Wolfe, president of CelebriDucks (asi/44398), which sources 75% of its custom rubber ducks from China but handles art pre-production and the remaining 25% in the U.S.

Since 2004, wages have been rising by 12% annually. By 2015, the average annual urban salary was over $9,000, and could reach $20,000 by 2020. Why the increase? While provinces and cities have the ability to set their own minimum wages, the greater culprit is that the cost of living has skyrocketed in many parts of the country. Laborers who previously had a surplus of money to send home to their families now have just enough to get by. Legions of workers no longer line up for the lowest-paying jobs. Chinese factories are paying more, and as they aspire to high-end manufacturing for industry, they are trying to attract better workers. “China factories are hiring office workers mostly with college degrees, who demand higher salaries in their sales departments and offices,” says Edith G. Tolchin, owner of EGT Global Trading, and who has been sourcing in China for over 25 years. “Even many China factory workers are young college grads who work for a few years to get their experience, and then move on to higher-salaried employment.”

Tolchin says there are at least double the sourcing options from a decade ago – not in actual factories, but rather as college-educated workers open their own trading companies and position themselves by identifying America’s greatest sourcing needs. Meanwhile, many factories are struggling to stay open, pushed to the financial brink by increased wages, China’s economic slide and decreased international demand. According to John Lombard, president of

Middle Kingdom Sourcing, the financial stress will create heightened competition among factories. “Increased competition is going to cause Chinese companies to improve or die,” says Lombard, who lives in the city of Dongguan and has been in China for 23 years. “We’re already seeing a significant trend toward Chinese companies focusing more on quality, customer service and more.”

However, this will weed out the lowest-quality producers – the ones who are also the lowest-cost providers. “If quality is not much of an issue for your product, and your primary concern is the lowest possible price, China is becoming less and less attractive,” Lombard says. “But if you want both good quality and good prices, China’s still a viable option.”

The sentiment is echoed by others: China as a manufacturing entity isn’t going anywhere. But the end of its low-cost production will force suppliers to reexamine their practices. Staying in China will have its downsides – increased costs, delayed lead times – but the country remains a well-oiled machine, with a robust infrastructure (upon which the country plans to invest billions more) and decades of experience. Other countries, by contrast, are growing and offer lower labor costs, but lack the same supply chain advantages.

When Wolfe created The Good Duck, a PVC- and phthalate-free rubber duck, he was able to make it for less in the U.S. than it would have cost him in China. Still, his custom painted rubber ducks are made in China, because the rotational molding of the ducks and the intricacies of painting are simply too expensive to do it elsewhere right now. But as China’s prices rise, Wolfe and other suppliers may have their hands forced. “In five years,” he says, “I think it’s going to be shocking for people.”